Explore the Rich History of the Seeder Nation

Here you will find an immersive look into the Seeder Nation’s origins, beliefs, and evolution. It emphasizes the foundational stories and core ideals that shape the community and inspire its continuing journey.

Serving as a proxy for our shared human culture, The Seeder canon provides a rich visual and thematic vocabulary for artistic exploration, while hopefully avoiding the pitfalls of commentary on existing sociopolitical institutions. Sculptures, dioramas, vignettes, and 2D works can draw directly from mythology, ritual practices, material culture, and communal life, while having the freedom to parody and criticize without restraint.

If successful, this exhibition uses the Seeders as a proxy society to explore the broader themes of: gender, nature, religion, politics, military, and consumer culture.

Section 1: Core Beliefs & Setting

Faith Names and History

- Vishnaism: Derived from the word “vishnya,” which means “cherry” in many Slavic languages. This is the founding religion which came to dominate Europe, West Asia, and North Africa

- The Seedling Reformation: A splintering of Vishnaism leading to the Seeder, Cyclists, and Planter faiths.

- Seeders: Immigrated to North and South Norema (America) in the 1650’s

- Groves: Communities/Congregations within the Seeder faith.

Sacred Centers

- At the heart of many Seeder groves is often a massive cherry tree, symbolic of life, death, and renewal. These trees are a variety bred from Japanese trees brought to Norema in the 1740’s. They adapted well to the climate of the south lands and grew to enormous size.

- Often gathering halls are built surrounding the Sacred Centers and ceremonies and festivals involve caring for and worshiping the trees.

- The tree’s seasonal cycles guide these rituals, festivals, and daily practices.

Worldview & Cosmology

- Seeders view agriculture and propagation as sacred acts; to grow food is to spread life and light.

- Humanity is part of natural cycles of bloom, fruit, decay, and rebirth, which shape both daily life and ceremonial observances.

- Seeders approach technological and societal change with caution. They are slow to adopt modern technologies, aware of the risks that rapid progress can bring. However, they are not opposed to modern conveniences and will integrate them thoughtfully when they serve community life and sustainability.

- Seasonal cycles, abundance and scarcity, and community survival are divine lessons embodied in nature.

Community Life

- Groves emphasize shared labor, collective meals, storytelling, and ritualized games as forms of devotion.

- Language and oral tradition blend folk wisdom, storytelling cadence, and agricultural lore.

Core Values

- Propagation: Seeds, literal or symbolic, must be spread.

- Cycle: Every season, bloom, and frost has sacred significance.

- Restraint: Not all growth is holy; excess can invite disruption.

- Communion: Eating, working, storytelling, and play are sacred acts.

Section 2: Mythology & Deities

Overview: Seeder mythology reflects the life cycles of cherries and their trees, embodying principles of growth, decay, renewal, and propagation. Stories, parables, and deities are metaphorical tools to teach ethics, patience, communal responsibility, and respect for nature. Just as rituals centering around cherry tree worship are purely metaphorical. No one in the Seeders believes these figures are truly supernatural; they are conceptual frameworks for understanding the world. They are touchstones for concepts and contemplation.

The Old Gods

From Vishnaism, we are given the ten gods of the traditional Cherry Tree Mythology, foundational in Seeder storytelling and lore. These figures are referenced in historical myths and allegories, serving as cultural touchstones as well as the basis for any rituals, the calendar and days of the week.

Read more about the Old Gods here.

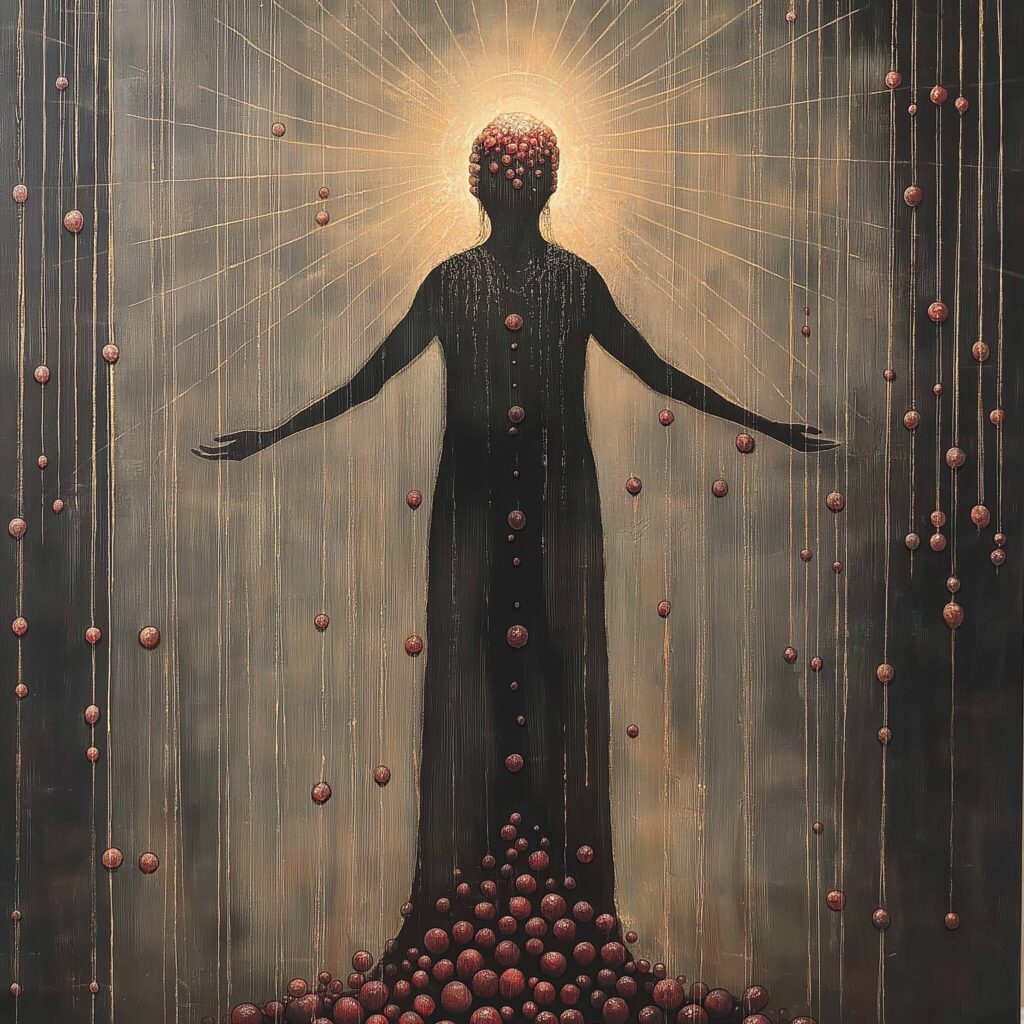

New World Deities

In the Seeder and Planter faiths we have ten additional figures used in contemporary groves to organize teachings, rituals, and seasonal observances. Serving as guides for reflection, communal values, and agricultural cycles:

- Brenara, Goddess of Bloom – Teaches hope, potential, and careful tending of beginnings.

- Fravik, Lord of Fruit – Teaches timing, generosity, and sharing bounty.

- Kelyth, Spirit of the Frost – Teaches patience and restraint; cycles of dormancy.

- Solvyr, Keeper of Seeds – Emphasizes propagation and spreading life.

- Thavren, Guardian of Decay – Teaches acceptance of endings and renewal.

- Mirelda, Mistress of Water and Growth – Encourages careful nurturing of life’s rhythms.

- Draven, Watcher of Shadows – Guides caution and thoughtful adoption of new practices.

- Elvra, Spirit of Harvest Feast – Represents community, sharing, and gratitude.

- Noryn, Keeper of Lore – Preserves stories, parables, and tradition.

- Pavrel, Trickster of Change – Embodies unexpected shifts and lessons learned from disruption.

Parables & Oral Lessons

Seeders communicate ethical and practical wisdom through stories linked to both Old Gods and New World Deities.

Common parables include:

- The Bloom Comes After the Frost – patience brings reward.

- The Gambling Vending Machine – warns against impatience and reliance on luck.

- The Parable of Abundance – teaches generosity and respect for natural bounty.

Divine Themes Across Groves

- Groves may emphasize different Old Gods or New World Deities depending on local culture, season, and storytelling tradition.

- The metaphorical framework reinforces connection to cycles, communal responsibility, and agricultural practice, not supernatural belief.

Section 3: Calendar, Rituals & Holy Days

The Calendar

The calendar for the seeders is rigid and unchanging. Daily life is cyclical and repetitive. Time is spent in work and in prayer, but just as much time is spent in leisure and socializing. The best of which are the amazing festivals throughout the year.

Learn more about the The Vishnaian Calendar here.

Seeder rituals and festivals are tied to the life cycles of cherry trees, the rhythms of agriculture, and community cohesion. Practices are symbolic and performative, often blending practical labor with ceremonial meaning. While some ceremonies historically involved literal acts, most modern groves use symbolic substitutes, reflecting moral and communal lessons rather than supernatural mandates.

Seasonal Festivals

Festivals correspond to stages of the cherry tree and the agricultural calendar:

- First Bloom Festival – Marks the emergence of buds in spring. Themes: hope, renewal, careful preparation.

- Ripening Feast – Celebrates fruit development and community cooperation. Activities: communal meals, games, storytelling.

- Harvest Ritual – Honors gathering and sharing of food. Emphasizes gratitude, distribution, and foresight.

- Zimrostva – Offerings of evergreen branches and frozen fruit, celebrating the return of the light with candles and bonfires,

symbolizing the coming spring - Seed Day – Celebration of propagation; exchanging seeds and small gifts to ensure growth and community continuity.

- Abundance Ceremony – Honors both the bounty of the year and the ethical responsibility to nurture life and community.

Cannibal Ceremonies (Literal & Symbolic)

- Seeders historically performed ritual consumption of human flesh in extremely controlled, sacred contexts, though symbolic substitutes are now more common.

- Each ceremony has paired recipes: one literal (historical/canonical) and one symbolic (modern/ethical).

Examples:

- The Feast of the Bloomed Heart

- Literal: Involves consuming the heart of a deceased community member.

- Symbolic: Substitute with a baked root vegetable shaped like a heart, sharing among participants to symbolize communal life-force.

- The Flesh of the Frosted Seed

- Literal: Ritual involving consumption of flesh to honor seasonal transition.

- Symbolic: Use roasted root meats (beef, pork, or plant-based analogues), preserving ceremonial form while removing literal cannibalism.

- The Offering of the Golden Cherry

- Literal: Rarely enacted; involves sacrificial sharing in small, controlled groups.

- Symbolic: Replace with a golden-colored fruit or pastry, shared communally as an act of gratitude and propagation.

Other Ritual Practices

- Proxies: Small stuffed figures representing people, intentions, or abstract forces. Used to influence affection, rivalry, or luck.

- Sacred Seeds: Carved wooden tokens hung near exits of buildings to protect and bless the space.

- Games & Competitions: Ladder-ball style games with walnuts on strings, reinforcing skill, patience, and playful ritual.

- Communal Storytelling & Parables: Oral transmission of cautionary and moral tales, often accompanied by seasonal work or meals.

Key Principles Across Rituals

- All rituals connect the individual to community and nature, reinforcing respect for cycles and agricultural labor.

- Symbolism outweighs literal belief; even historically extreme practices are now primarily teaching tools and performance.

- Flexibility is common: groves adapt rituals to local resources, ethical standards, and seasonal conditions.

Section 4: Objects & Material Culture

Objects and artifacts in Seeder groves serve symbolic, ritual, and practical purposes. They reinforce community values, agricultural cycles, and mythic lessons, and often feature in festivals, games, and parables.

Key Objects

- Proxies

- Small stuffed figures representing people, intentions, or abstract forces.

- Used for ritual influence, such as fostering affection, rivalry, or luck.

- Not considered magical; their power is symbolic and psychological, reinforcing focus and intention.

- Sacred Seeds

- Carved wooden tokens representing protection and fertility.

- Typically hung near exits of buildings to bless and guard the space.

- Sometimes given as gifts to encourage propagation and continuity.

- Sacred Ladders

- Rough-branch ladders of varied shapes, used in games and ritual competitions.

- Games resemble ladder ball, but with walnuts on strings.

- Emphasize skill, patience, communal engagement, and reflection on natural cycles.

- Objects of Lore

- Includes items like the beautiful old box filled with dried cherry seeds and trinkets.

- Objects carry ancestral memory, symbolic meaning, and storytelling potential.

- Often displayed during festivals or used in parables to illustrate moral lessons.

- Ritual Implements

- Tools used for planting, harvest, and ceremonial preparation.

- Often decorated or inscribed to indicate sacred purpose, linking practical work to spiritual meaning.

- Symbolic Food & Offerings

- Fruits, vegetables, baked goods, and other foodstuffs are ritual objects in feasts and ceremonies.

- In symbolic cannibal ceremonies, foods are shaped or presented to stand in for human elements, maintaining ceremonial structure ethically.

- Paraphernalia for Parables & Storytelling

- Figures, small sculptures, and objects referenced in oral tales.

- Provide a visual and tactile anchor for teachings, helping embed moral and agricultural lessons in memory.

Material Principles

- Objects are functional and symbolic, not magical.

- Craftsmanship reflects care, reverence, and skill, linking the maker to community and seasonal cycles.

- Objects are contextual and adaptive; each grove may reinterpret or modify items according to resources, local traditions, or ritual focus.

Section 5: Texts & Oral Tradition

Seeders preserve knowledge, ethics, and history through oral tradition, written and crafted texts. Stories, parables, and teachings are designed to guide community life, agricultural practice, and moral reflection. Texts and sermons are practical, ethical, and symbolic, not doctrinal commandments.

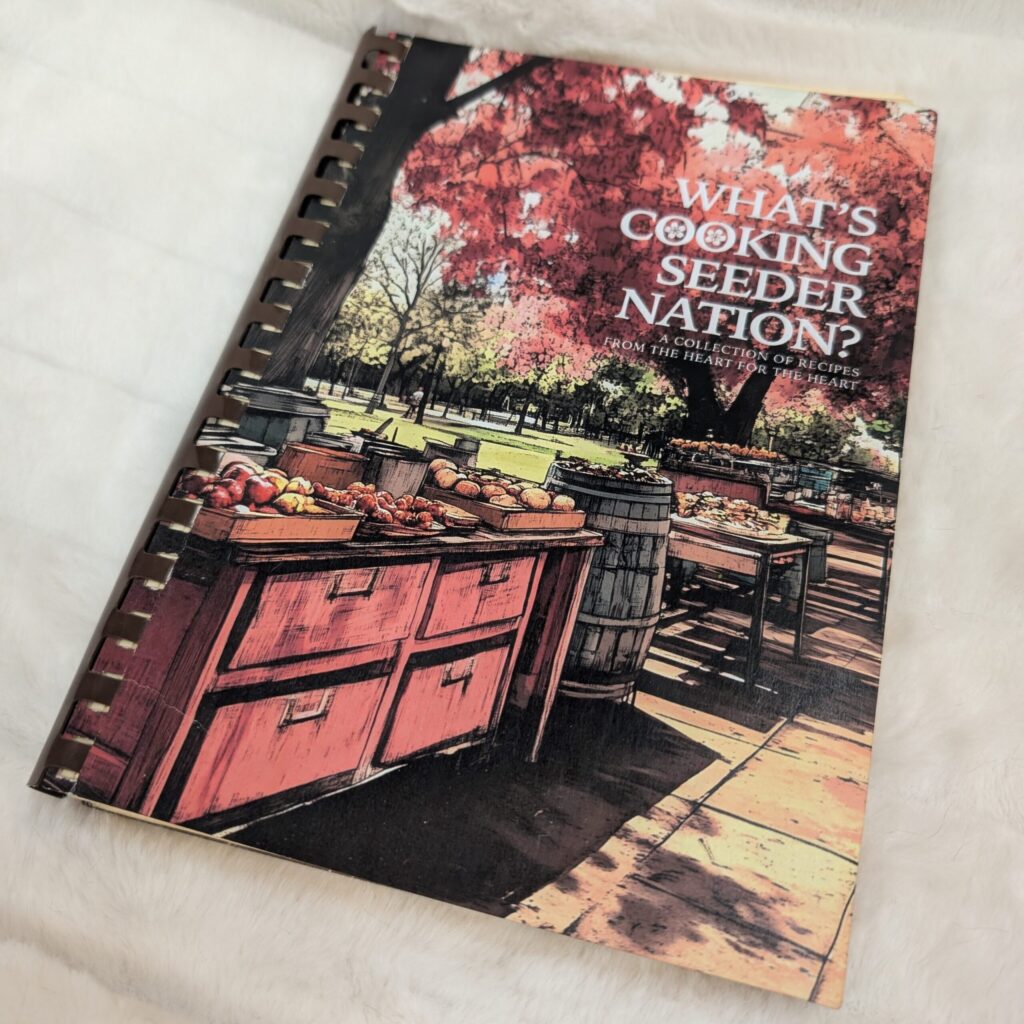

Cookbook as Sacred Text

The Seeder cookbook combines recipes, parables, anecdotes, and ritual instructions. It is both a practical manual for daily life and a repository of communal memory. Includes instructions for seasonal foods, communal meals, and symbolic cannibal ceremonies (with literal and substitute versions). Anecdotes often recount grove life, moral lessons, and community wisdom.

Radio and Television Sermons

- Sermons are delivered in a “Panter-Appalachian” style, blending rhythm, cadence, and emotional performance.

- Typically include sound cues, repeated phrases, and pauses to encourage reflection and participation.

- Sermons reinforce community values, seasonal cycles, and ethical conduct rather than supernatural belief.

Parables

- Central teaching tools, often tied to Old Gods, New World Deities, or agricultural cycles.

- Examples include:

- The Bloom Comes After the Frost – patience leads to reward.

- The Parable of Abundance – generosity and care for natural bounty.

- The Gambling Vending Machine – warns against impatience and reliance on chance.

- Examples include:

- Parables are adaptable: groves may reinterpret them for contemporary lessons.

Storytelling Practices

- Oral storytelling is communal and performative, often accompanied by ritual work or games.

- Stories are preserved through memorization, performance, and material objects (figures, tokens, or props).

- Teachings are practical, symbolic, and flexible, allowing adaptation across time and place.

Transmission Principles

- Knowledge is shared intergenerationaly, with emphasis on lived experience and observation of cycles.

- Groves maintain continuity while allowing local variation, reflecting environmental conditions, cultural context, and community priorities.

Section 6: Social Structure & Community Life

Seeder groves are community-focused, balancing individual labor, shared responsibility, and ethical guidance through tradition. Social structures are flexible, adapting to local conditions, population size, and available resources.

Grove Organization

- Each grove functions as a semi-autonomous congregation.

- Leadership is typically rotational or consensus-based, rather than rigidly hierarchical.

- Roles include:

- Caretakers – manage the grove’s cherry tree(s) and agricultural cycles.

- Storytellers/Oral Historians – preserve parables, myths, and local lore.

- Ritual Coordinators – organize festivals, feasts, and ceremonial practices.

- Craftspeople – create proxies, sacred seeds, ladders, and ritual implements.

- Educators – teach practical skills, agricultural techniques, and moral lessons.

- Roles include:

Community Norms & Values

- Cooperation, labor sharing, and reciprocity are central to social cohesion.

- Individual actions are evaluated in terms of their impact on cycles, growth, and communal well-being.

- Storytelling, games, and shared meals reinforce relationships and ethical principles.

Taboos and Cautions

- Seeders exercise caution with rapid technological adoption, reflecting concern for societal and environmental consequences.

- Overreach beyond natural or social cycles is approached with careful deliberation, not forbidden.

- Ethical norms guide behavior regarding food, ritual participation, and communal responsibilities.

Lifecycle and Initiation

- Members are integrated into grove life through participation in planting, harvest, and seasonal festivals.

- Children learn through observation, storytelling, and symbolic games that encode moral and practical lessons.

- Rites of passage often include symbolic planting, participation in feasts, or learning key parables.

Conflict Resolution and Justice

- Disputes and offenses are addressed with punitive measures rather than purely restorative methods.

- Punishments are intended to maintain social order, respect for cycles, and community cohesion.

- Common punishments include:

- Hanging stockades – the most frequently used method for lesser offenses.

- Lashings – for severe offenses.

- Confinement – temporary restriction of movement or access.

- Exile – banishment from the grove.

- Being buried to the neck in grain – temporary punishment emphasizing humiliation and endurance.

- Loss of property – forfeiture of land, tools, or goods.

- Execution – reserved for capital crimes.

Flexibility and Local Variation

- Groves adapt practices to environment, population, and cultural context.

- While core values and parables remain consistent, rituals, games, and material culture may differ.

Every Seeder in the Grove Has a Story to Tell

Meet the influential minds shaping the Seeder Nation experience.

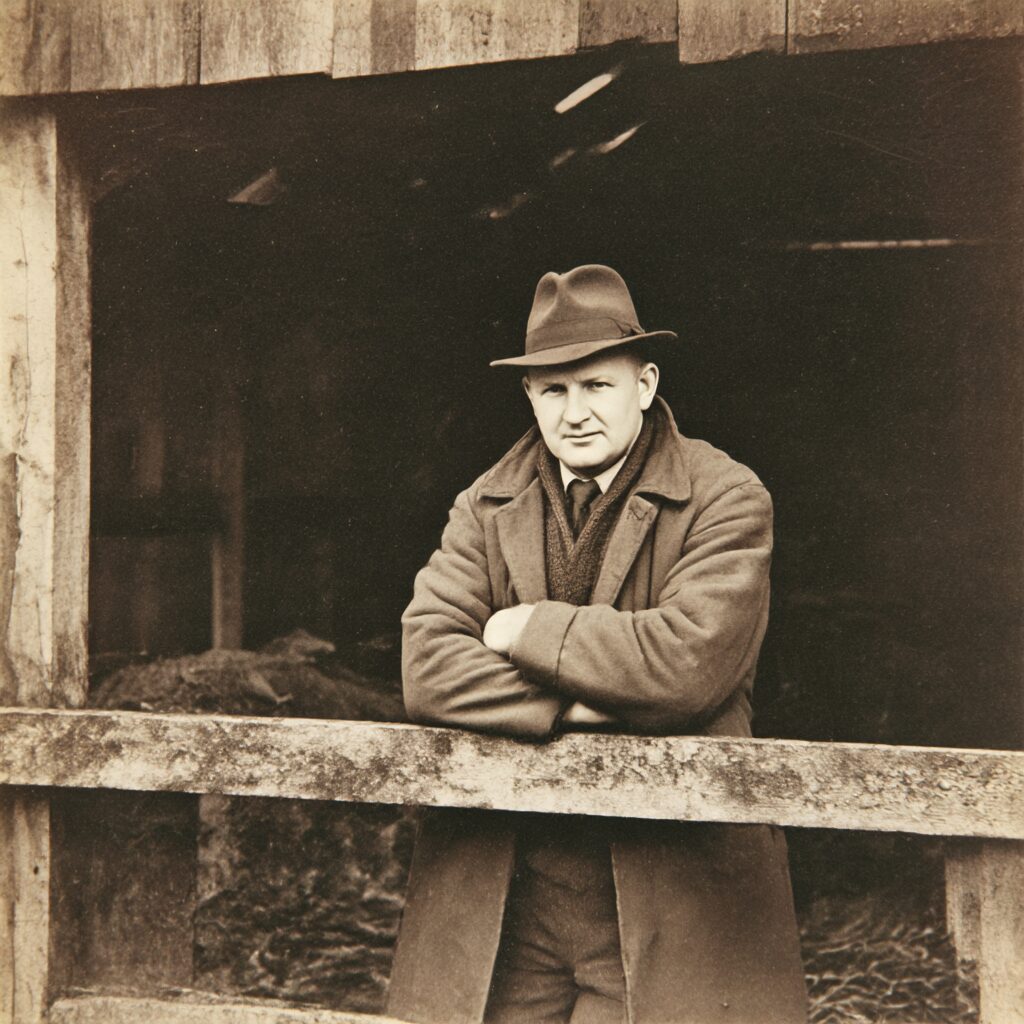

Ezekiel “Zeke” Harper

Archivist

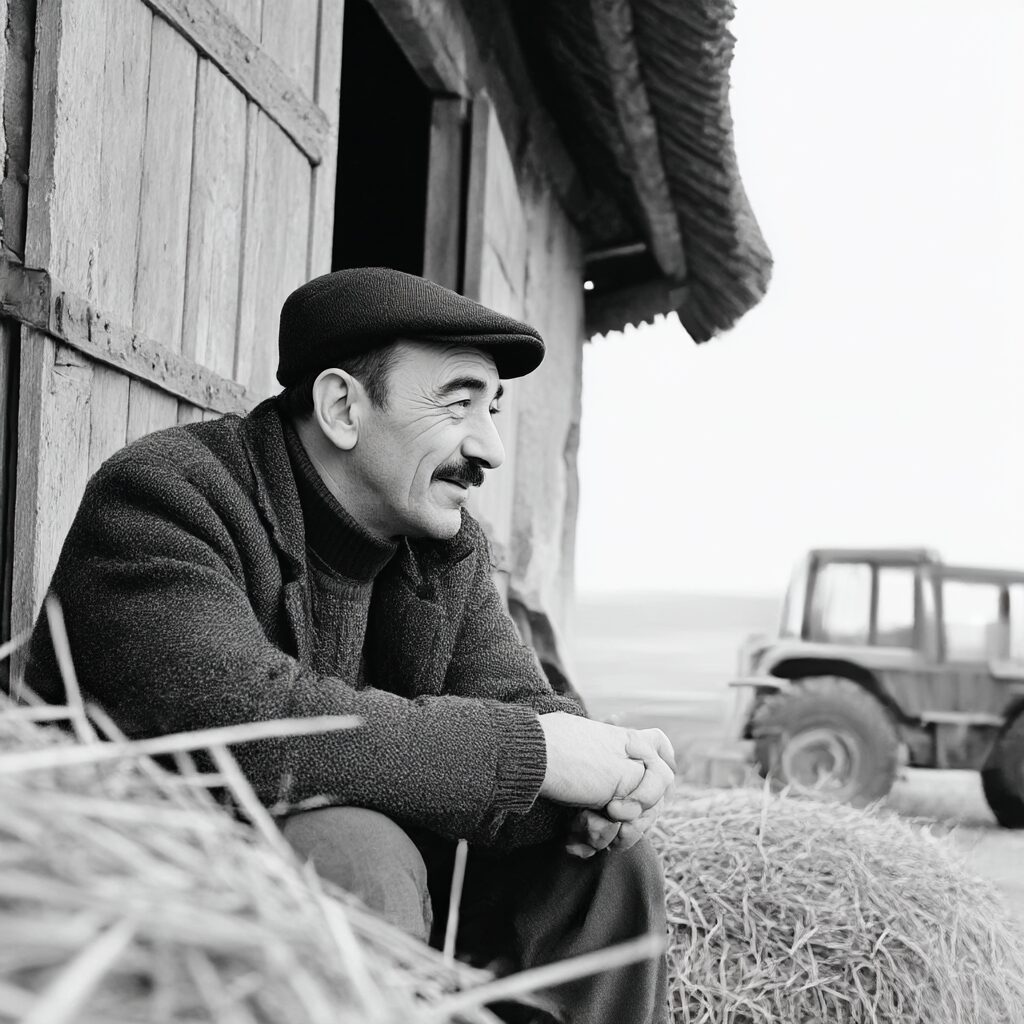

Samuel Yoder

Seed Keeper

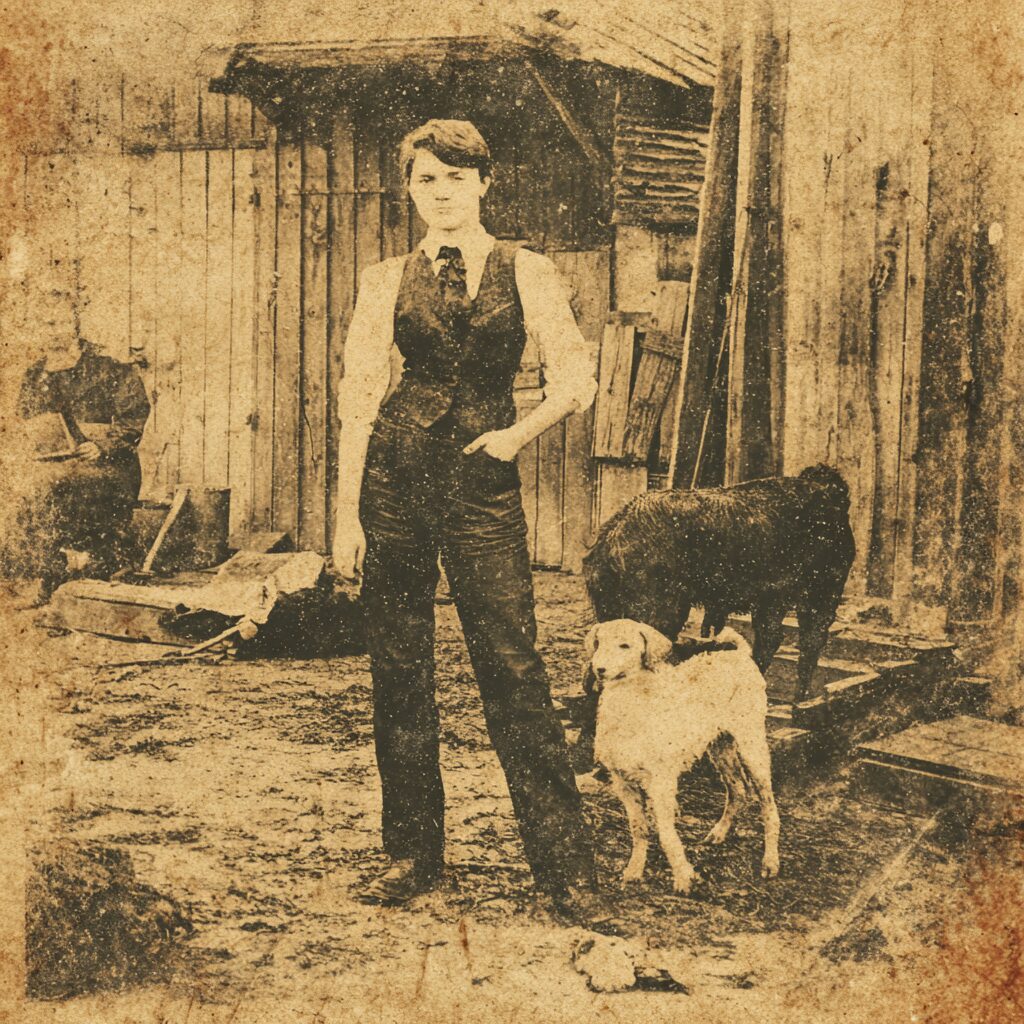

Miriam Tiller

Scroll Manager

Julian Crest

Founder of the Women’s Conclave